This blog post is a refined transcription of the presentation Zalim Bashorov and I gave at Wasm I/O 2023 to introduce Kotlin/Wasm. The recording is also available on YouTube.

Intro Link to heading

Zalim Hi, everyone! I’m Zalim. I’m writing Kotlin in Kotlin at JetBrains and leading Kotlin/Wasm. We are going to have a quick journey around Kotlin/Wasm. We will see what the possibilities there are and also have a look at the inside.

Sébastien Hey, I am Sébastien Deleuze, I work as a Spring Framework committer at VMware. I led the introduction of Kotlin and GraalVM native images in Spring, but today, I am going to talk about the work I do on Kotlin/Wasm as a side project.

Let’s begin with a quick presentation of the language. Kotlin is a modern statically-typed and garbage-collected language. It manages to be both concise and expressive, has a pragmatic mindset while remaining elegant, and has found, in my opinion, the right balance between imperative and functional programming. One of its key features is that it turns the billion-dollar mistake (null references) into build-time null-safety to check the presence of a value.

The widest adoption of Kotlin is on mobile, since Google has chosen Kotlin as the official language for Android. On the server-side, Java remains the leader, but Kotlin has a significant market share, and a lot of Spring developers are using Kotlin to develop their Spring Boot applications. Thanks to its DSL and scripting capabilities, Kotlin has also been chosen as the language used to describe Gradle builds.

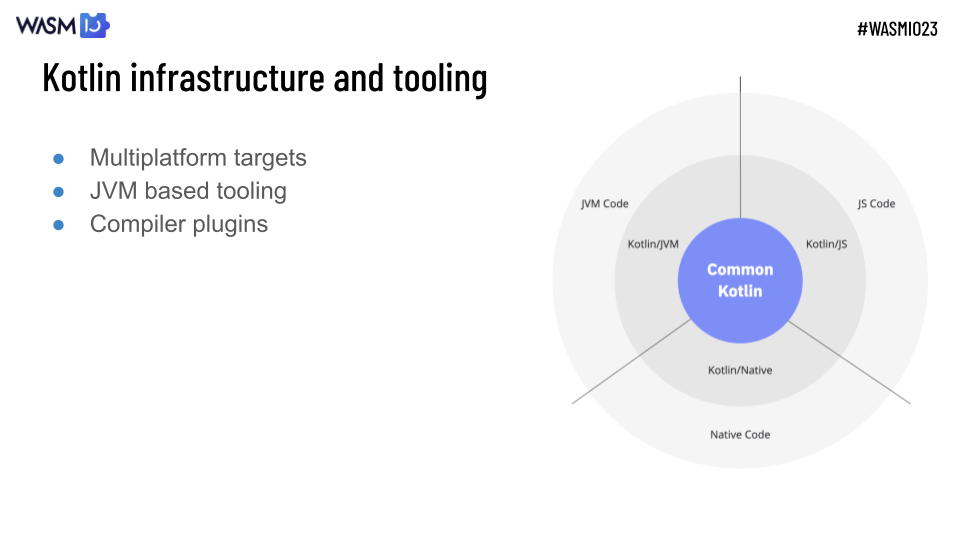

Even if the most successful use-cases are targeting the JVM, Kotlin has dedicated support for developing multiplatform projects. You write common code that will be shared, then add the required specific bits for the platform(s) you target (JVM, JavaScript, Native). Its tooling is mostly JVM based. Kotlin provides a compiler plugin mechanism capable of powerful build-time transformations.

Let me share a story with you. Since I work in this industry, I have always tried to find solutions to avoid tech silos and to allow sharing code for various usages. So, when I saw the ongoing standardization of WebAssembly in 2016, I immediately thought it would be a great opportunity for Kotlin. I shared this idea with the Kotlin team and community, and have been dreaming of dedicated support for WebAssembly in Kotlin since.

Kotlin/Wasm Link to heading

After an initial WebAssembly support prototype in Kotlin/Native leveraging the LLVM toolchain, the Kotlin team chose to introduce dedicated support for WebAssembly by targeting WasmGC in a brand new dedicated compiler. Kotlin/Wasm reached experimental status in early 2023, a few weeks ago.

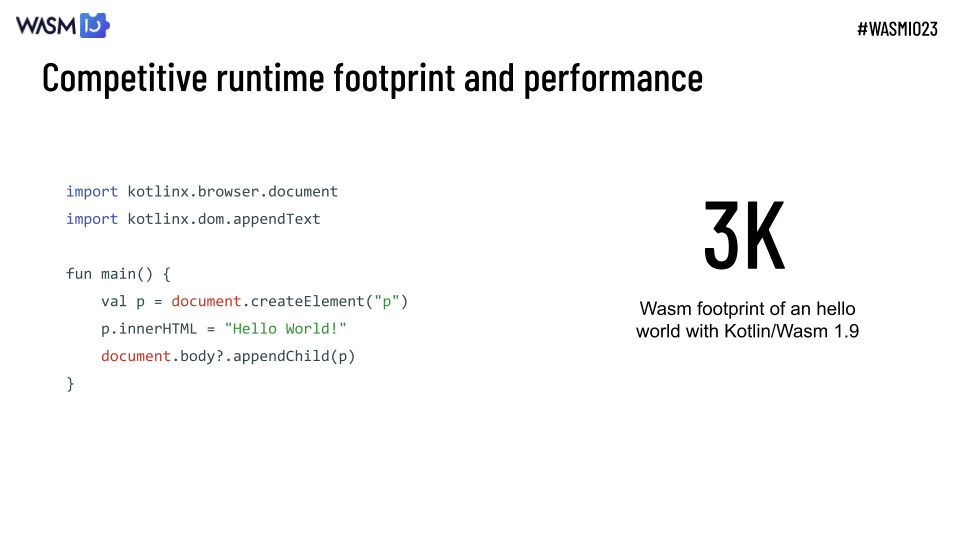

Kotlin/Wasm has been designed to provide a competitive runtime footprint and performance, in order to be able to target use cases where that’s critical. For example, the footprint is super important for public websites, and the great potential of the platform is illustrated by this super tiny 3K wasm file generated for a simple hello world like this.

Zalim, can you share more about this shiny new Kotlin to Wasm compiler?

Zalim Sure! Thanks Seb!

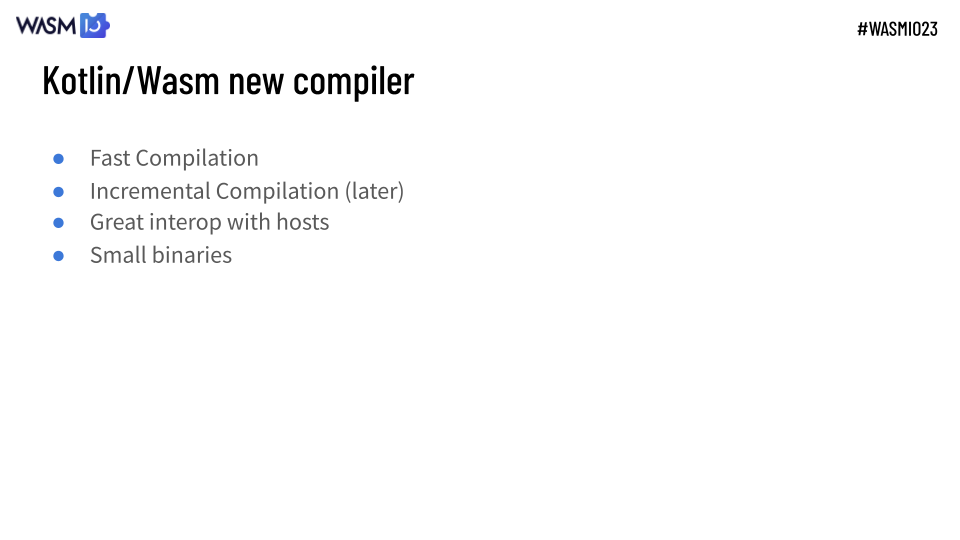

We built the new compiler from scratch, and we are targeting the next goals. We wanted to have fast compilation, because we think it’s important to have a sub-second round trip time and to achieve that we generate binaries directly and later going to make it incremental. We don’t do many optimizations during development but use Binaryen to optimize release builds. We also wanted to have small binaries and great integration with hosts, for example, to avoid leaks with cross-module links. And modern shiny proposals help us a lot with it.

We are using the following proposals.

Reference types which introduces basic reference types and instructions to work with them. It’s already part of the core specification and implemented by most VMs.

Next, the exception handling proposal, as you can guess, introduces something like exceptions and a way to throw and catch them. It’s in phase 3 out of 4, but it’s available by default in all major browsers.

Typed Function References, the name speaks for itself. It adds better typing for function reference and the instruction to call functions by reference. It’s in phase 3.

And last but not least – Garbage Collection proposal, interestingly the proposal has only one sentence about garbage collection. But it introduces high-level concepts required for languages and runtimes with GC. Such as structures, fields, references, and so on. Also in phase 3.

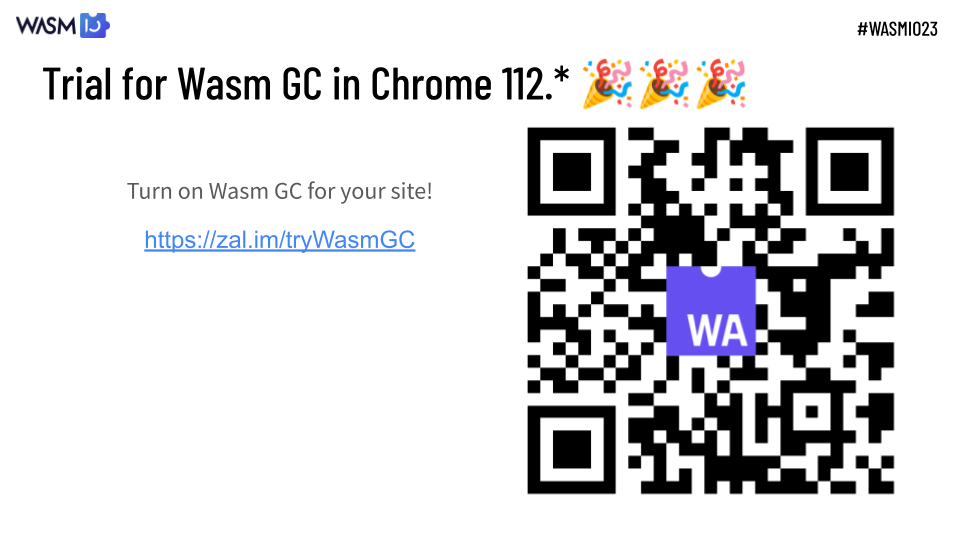

We have great news to share! Origin trial for WasmGC in Chrome is open for registration starting today. It allows you to turn on Wasm GC for your site. Follow this link for more information.

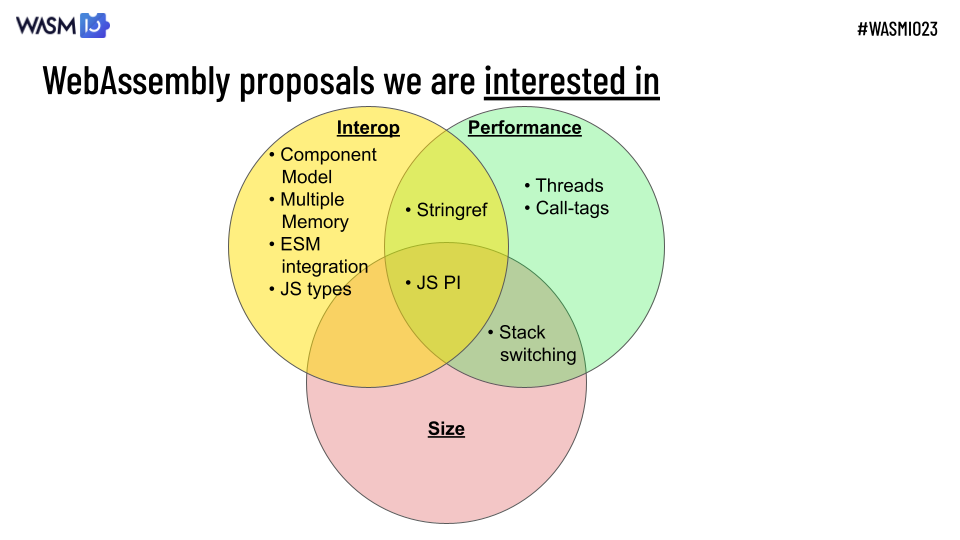

WebAssembly evolves continuously, and there are many new proposals. Some of them are interesting to us, and even more, we are experimenting with some of them. Let’s quickly look at them. There are many proposals aimed to improve interop with the external world. Performance is important as well. You can say nowadays disk space is cheap, and networks are fast, but there are use cases where size is still important, for example, the web.

I’d like to highlight a few proposals:

- First, Component Model because I personally think it’s important for the whole wasm ecosystem.

- Next, Multiple Memory – because it can unblock some interop cases, for example, between different languages.

- And, stringref proposal – I’ll explain it a bit later.

Inside Kotlin/Wasm Link to heading

Let’s take a deeper look at some Kotlin/Wasm implementation details.

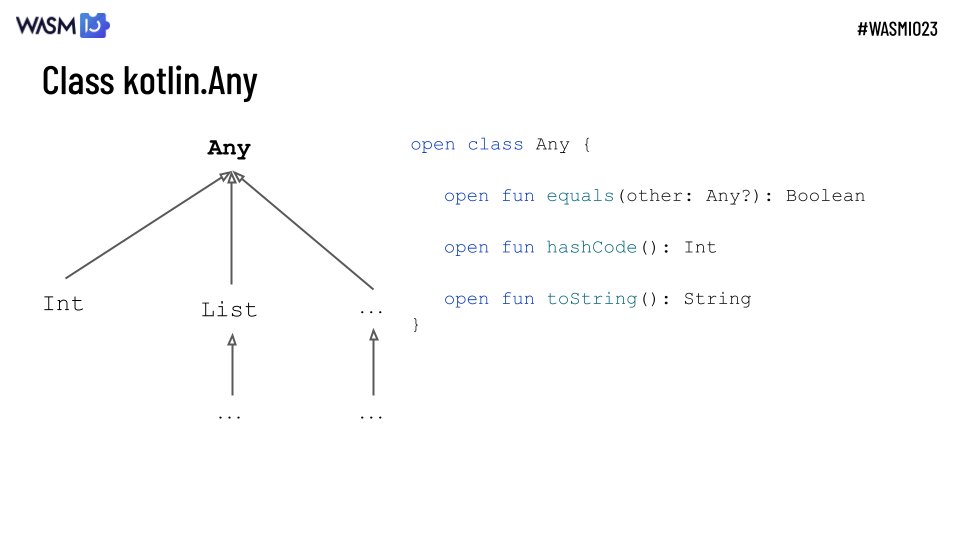

We start from kotlin.Any, it’s the base type for everything in Kotlin. Like java.lang.Object but better :) From the Kotlin developer point of view it has only 3 functions and no fields.

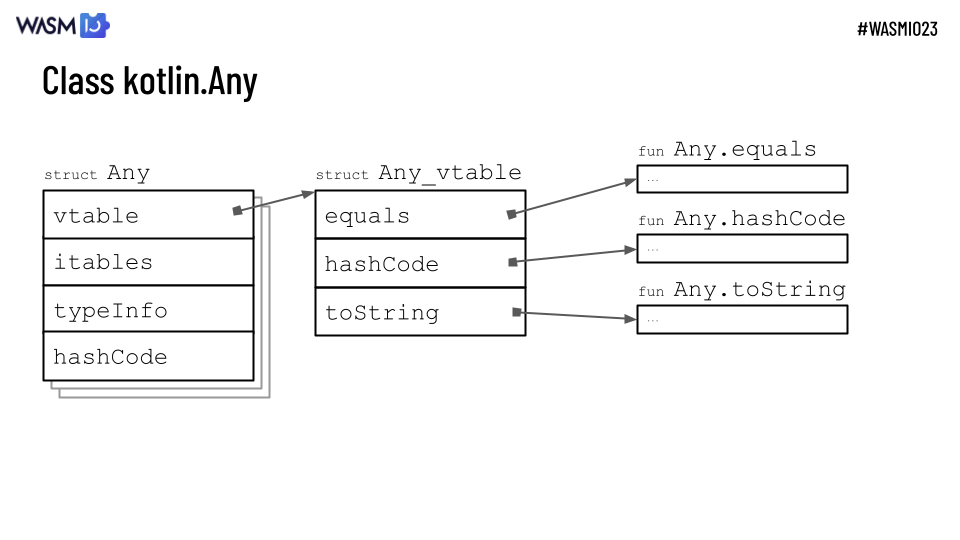

But actually from a Wasm point-of-view, it’s structured with 4 fields, so every instance of Any has these 4 fields.

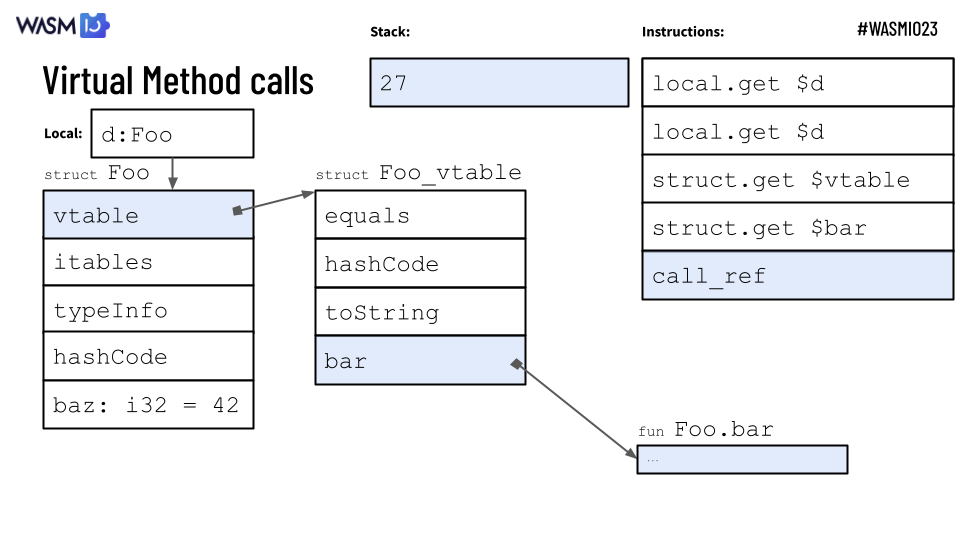

vtable field refers on a vtable structure for the specific class, now it’s Any’s vtable. All instances of Any shares one instance of the vtable structure with references to the specific function implementations. Virtual table used for dispatch virtual calls.

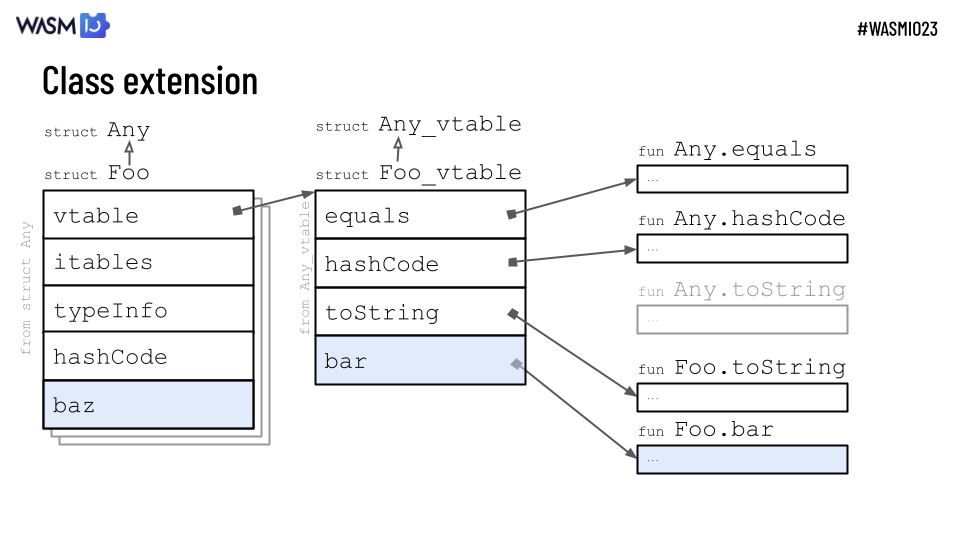

Let’s introduce another class Foo extending Any with one more field. In wasm, we extend Any structure, repeat the fields from Any, and introduce the new one. We also want to change some methods and add a new one. To achieve that, we introduce a new virtual table and change the type of the original vtable field to a more specific one to avoid casts while accessing the new vtable field. In the new vtable, we change the reference for toString and introduce a new field bar for the new method.

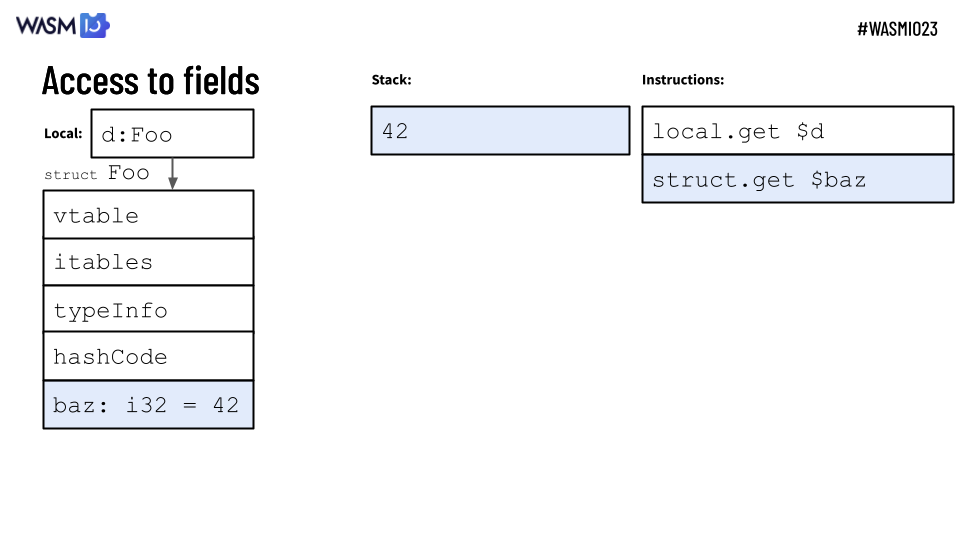

Ok, how to access fields and call methods? Accessing fields is simple. Say we have a local variable

Ok, how to access fields and call methods? Accessing fields is simple. Say we have a local variable d referencing an instance of Foo. We have a stack for values and instructions to execute. First, we need to put a reference to the stack using local.get. Then we use struct.get to access the field. It takes the reference from the stack, reads the field, and puts the value to the stack. Easy!

To do a virtual call, we need a bit more. We have the same variable d with an instance of Foo, and now we want to call the method bar. We put d on the stack 2 times. The first is an argument of the method. The second will be used to reach the method. Next, we read vtable field from the instance. Then, read bar from vtable. And finally, we can call it and see a result to the stack.

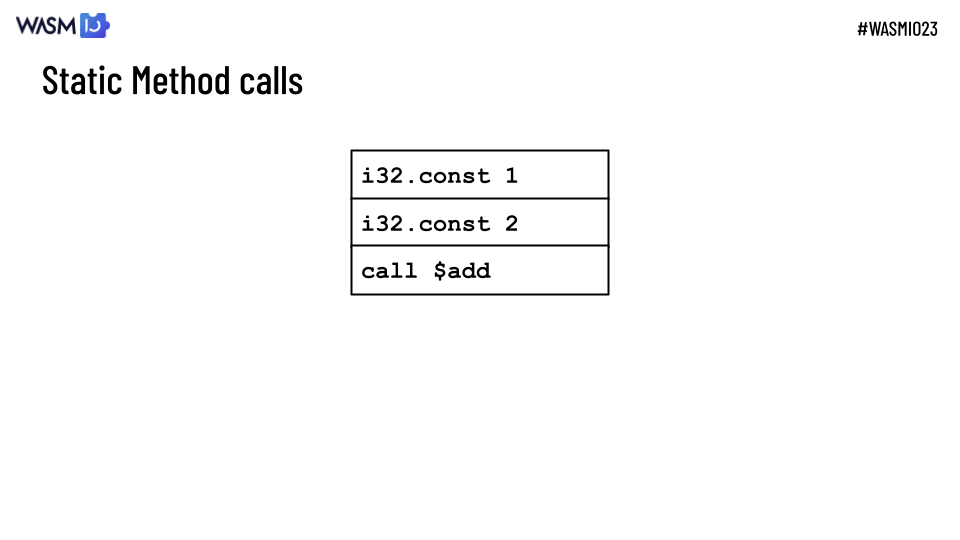

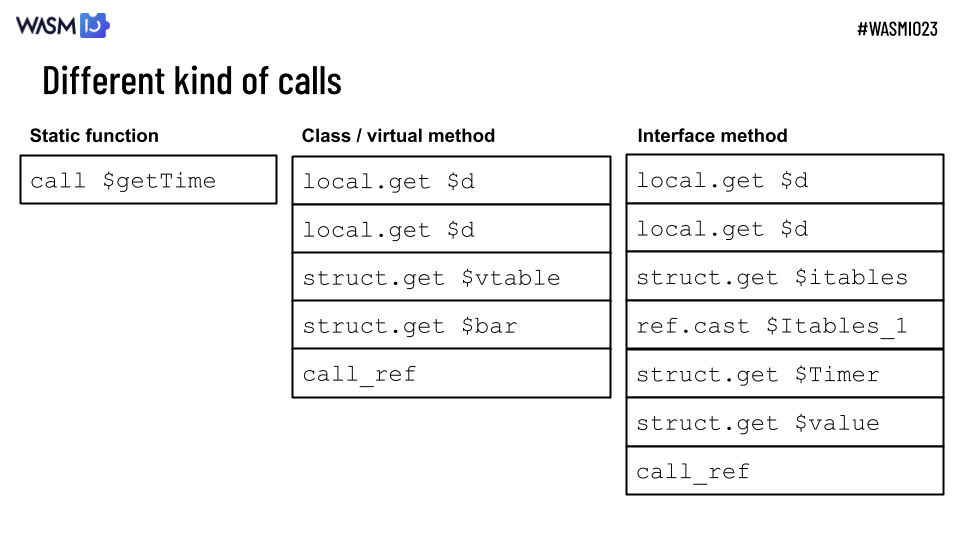

For comparison, a static call of function we know at compile time requires only 1 instruction. Of course, if a function has parameters, we also must put arguments on the stack.

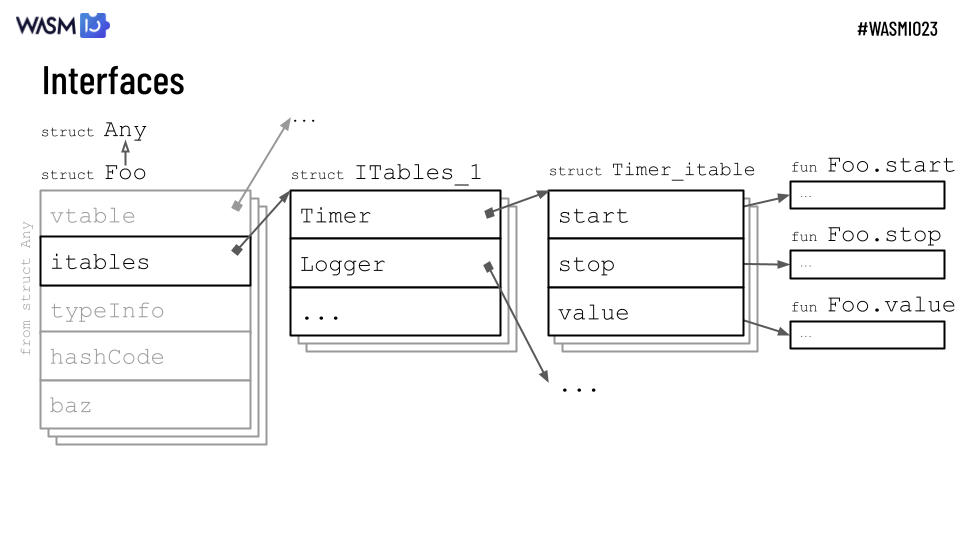

Kotlin also has the concept of interfaces, and it’s much trickier. Let’s say, the same class Foo, is implementing interfaces Timer, Logger, and maybe something else. So, we introduce a new structure ITables_1 with fields for each implemented interface. For each interface, we have a separate structure similar to vtables with references to actual implementations. Calling an interface method is similar to virtual one, but needs slightly more instructions.

Here is a comparison of different calls. It gives a good sense of the cost of calls, but be careful – it does not necessarily mean that, for example, every virtual call is 5 times slower than every static call. There are many aspects that could affect your runtime performance.

Let’s move to string internals. Most real-world applications work with strings a lot. So string implementation may have a big influence on the performance and memory usage of an application. At the start, we had a simple naive implementation which is just a wrapper over an array of chars. And it’s good both in terms of memory footprint and performance, except for concatenation. It’s a popular operation over strings. Doing concatenation over default strings, especially in hot paths, is considered bad practice in many languages, and those languages have special types for such cases, like StringBuilder in Kotlin. Anyway, writing a concatenation is much simpler, and it’s easy to underestimate the hotness of code.

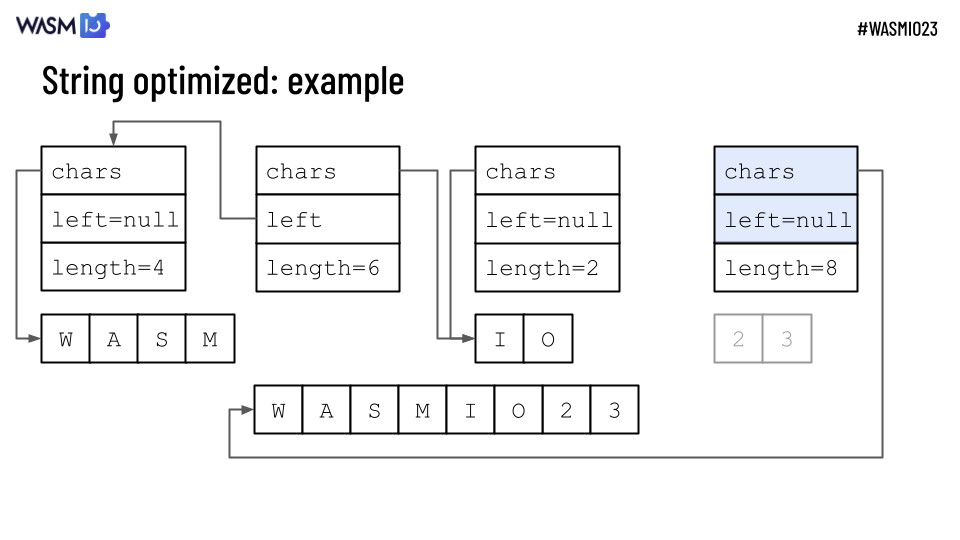

So, to optimize this use case, we changed the String representation by adding optional references to the prefix and length. Assume we have two strings WASM and IO. If we concatenate them, we will get an object referencing the left string and share the array with the right one. It could be chained like this, until we fold it. It’s folded on demand on all other operations Now it’s good on concatenations. In the future, we can consider improving builtin String for over cases, but there is a better option.

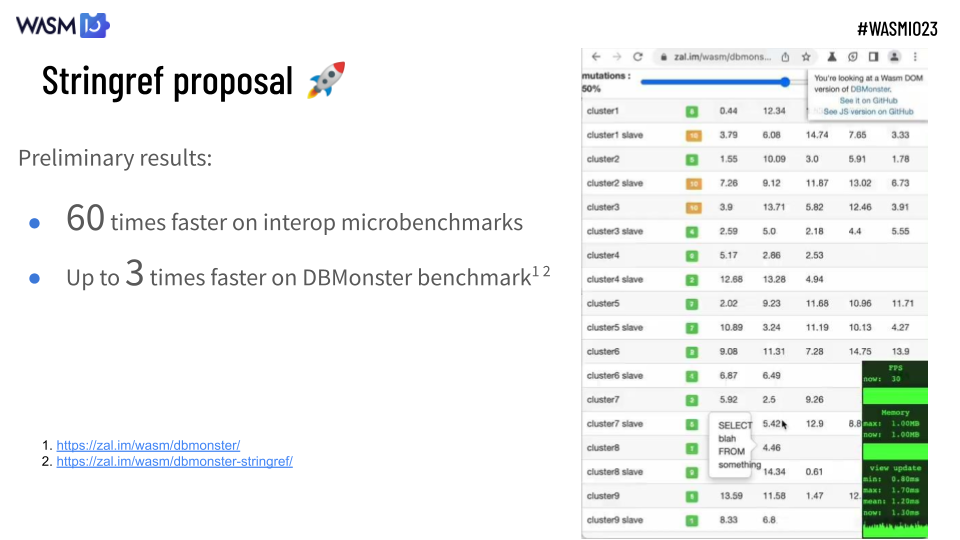

This better option is the stringref proposal.

The preliminary results of our experiments are promising:

- 60 times faster on interop microbenchmarks

- And up to 3 times faster on DBMonster (see benchmark without stringref versus with stringref) which works a lot with the DOM

Kotlin/Wasm usages Link to heading

Let’s move out and look at what is already possible to do with Kotlin/Wasm and the exciting related opportunities.

Compose Multiplatform Link to heading

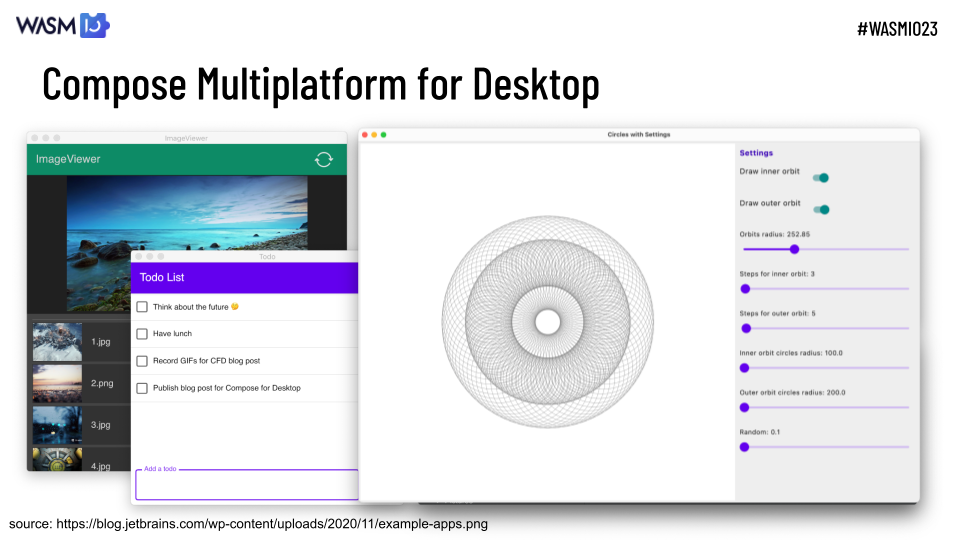

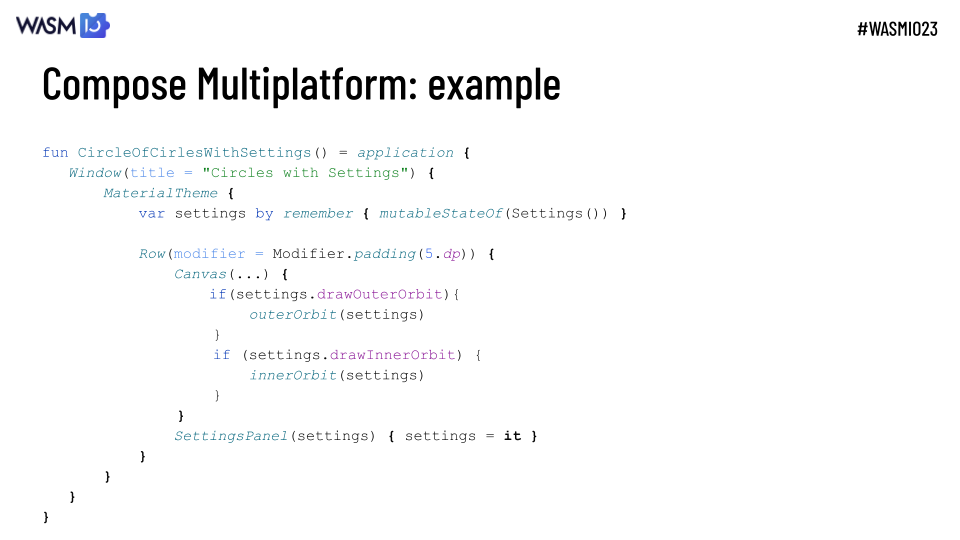

It is Jetpack Compose, a declarative UI toolkit in Kotlin, developed by Google for Android

Some time ago, a team at JetBrains took it and made it multiplatform

So now, you can write multiplatform application and use Compose for UI by writing code like on this slide.

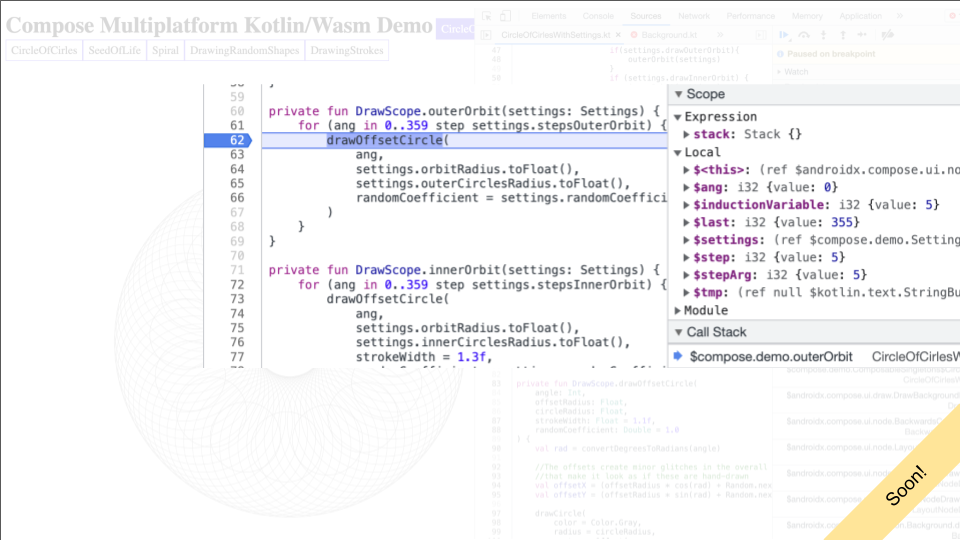

And it now works with Kotlin/Wasm! Check it out! It’s a demo originally built for desktop but run inside the browser, you can follow this link and play with the live demo. It works in Chrome and Firefox latest stable versions, but may require enabling WebAssembly GC support.

Even more, you will soon be able to debug it over Kotlin sources, inspect local variables and call stack, etc. Now it’s your turn to show cool things, Seb.

KoWasm Link to heading

Sébastien Thanks Zalim!

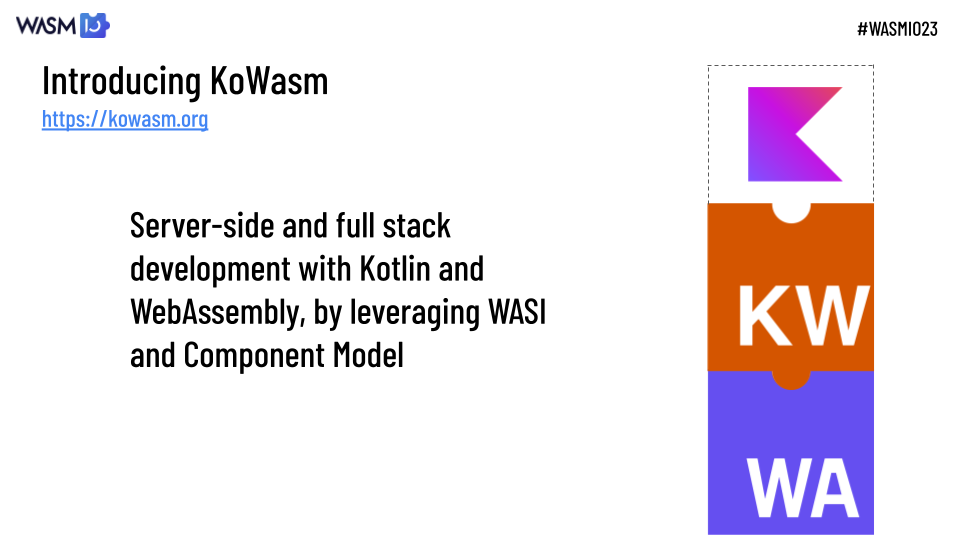

Kotlin/Wasm, for now, mostly targets web browsers, but I think it has a huge potential for other kinds of workloads. So earlier this year, I took the decision to create a new side project to explore this in collaboration with the Kotlin/Wasm team. That’s also for me a fun way to grow my expertise on what could be possible with WebAssembly, Java and Spring. So today, I am pleased to introduce KoWasm.

KoWasm’s goal is to explore server-side and full stack development with Kotlin and WebAssembly. It leverages WASI to access system resources and WebAssembly Component Model for the interoperability.

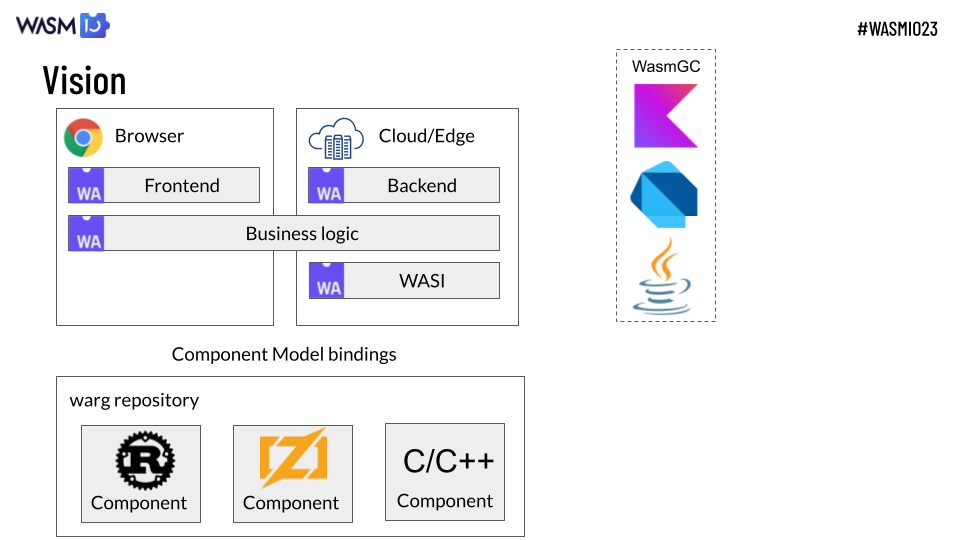

The vision behind KoWasm is not limited to Kotlin, and is an opinionated anticipation of what could be the WebAssembly ecosystem in the future.

I tend to think that once WasmGC is available in browsers and standalone WebAssembly runtimes, we will gradually see more and more applications written with languages targeting WasmGC like Kotlin, Dart, or Java. WebAssembly could be used to deploy workloads everywhere: browser, cloud, edge with business logic easily shared.

Given WebAssembly “share nothing” approach, WebAssembly components will IMO mostly be implemented with languages closer to the metal, with no or very little runtime, like Rust, Zig, C and C++. Those components would be exposed via warg repositories, a bit like NPM for JavaScript or Maven Central for the JVM, but in a more decentralized fashion.

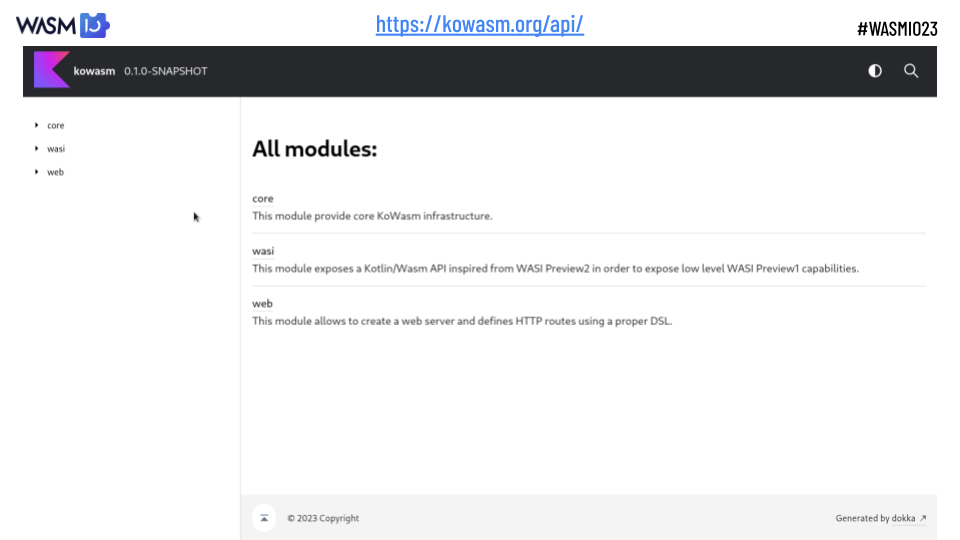

KoWasm provides and documents on https://kowasm.org/api/ APIs designed to allow building server-side applications.

The WASI module, for now, leverages the low-level WASI Preview1 ABI and exposes it with a Kotlin API inspired from the higher-level WASI Preview2 API. Later the goal would be to have WASI supported directly in Kotlin/Wasm.

KoWasm also exposes a web server API that allows to define HTTP routes and handlers in functional style. A lightweight HTTP client usable on frontend or backend will likely be included as well.

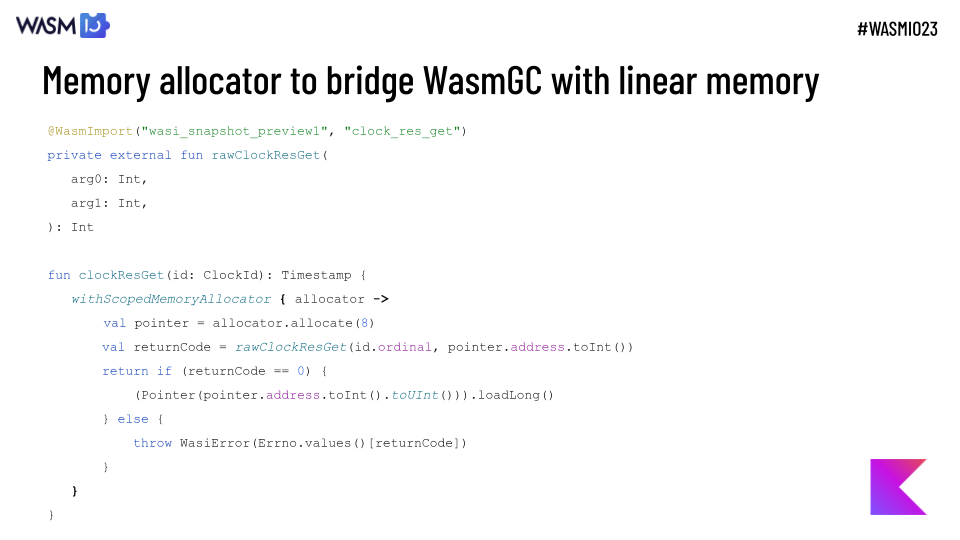

If we have a deeper look at the WASI module, it is implemented by using a memory allocator API provided by Kotlin Wasm. It allows making a bridge between WasmGC and the linear memory, and also leverages Kotlin/Wasm capability to import Wasm functions.

Let’s see a demo of what it looks like to create a server-side application with KoWasm.

So basically you create a Kotlin multiplatform project, indicate that it targets Wasm, and declare a few dependencies on KoWasm and some Kotlin multiplatform libraries. We can then see our domain model illustrated here by the User data class, with related validation logic created with the Konform multiplatform library. Such logic can be shared between the frontend and the backend. We also have a “fake” UserService class that exposes findAll and findOne functions.

We then create our server-side web application with a DSL where we declare HTTP routes and define HTML content with a Kotlin DSL inspired from Spring functional APIs where we can mix a declarative API with full autocomplete with regular Kotlin code like users.forEach. For now this web application runs via NodeJS WebAssembly support, but it will shortly require only WASI socket support.

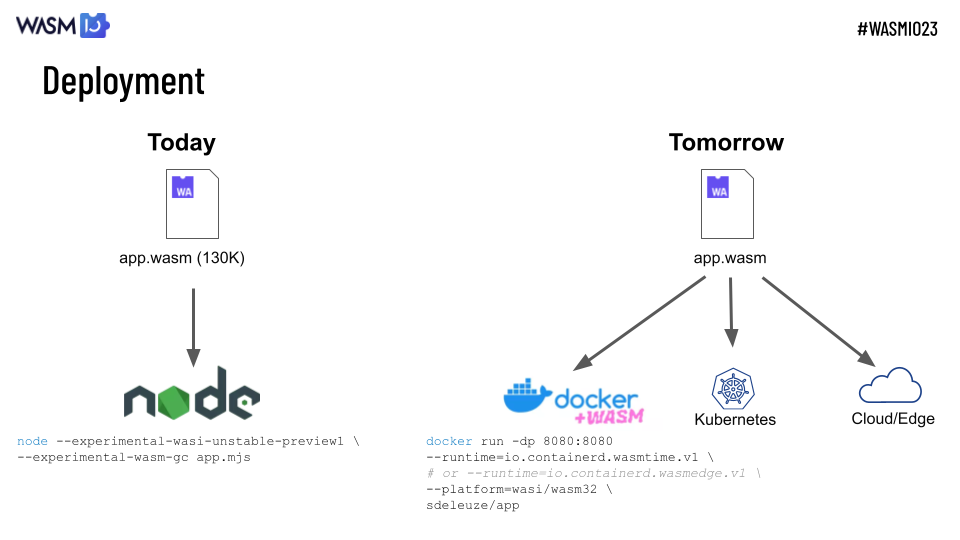

We then compile it via Gradle and Kotlin/Wasm compiler to a couple of Wasm and JavaScript files, and run it via Node.js with few experimental parameters.

For now, we deploy KoWasm applications to Node.js because we need a runtime that supports both WASI and WasmGC. But as soon as WebAssembly runtimes like Wasmtime or WasmEdge start to support the garbage collection proposal, we will be able to target those runtimes, and implement HTTP support purely using WASI, no JavaScript or Node.js API involved. Deployment could target Docker via its Wasm support, Kubernetes, Cloud or Edge platforms.

The key point here in terms of efficiency, security, and flexibility, is that we will be able to deploy directly a Wasm file that leverages WASI instead of a container and its operating system layer.

Combined with capability-based security and micro-seconds instantiation time, it is going to be, in my opinion, a game changer for server-side workloads.

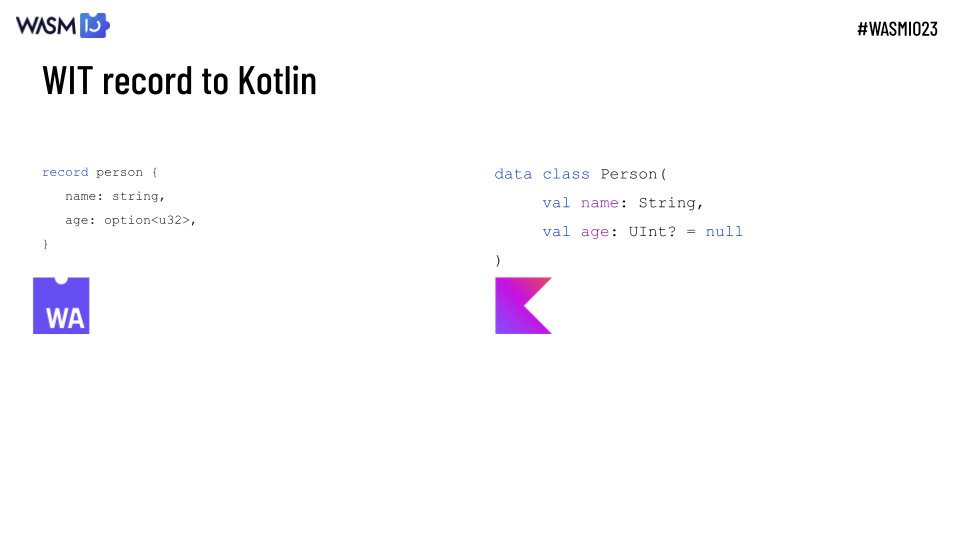

We have begun to think about how WIT, the format powering WebAssembly Component Model, would translate to Kotlin. And it looks like a pretty good match so far.

For example, WIT records can translate conceptually to Kotlin data classes.

WIT options translate nicely to Kotlin null-safety, and we can even use parameter default values to provide a better developer experience.

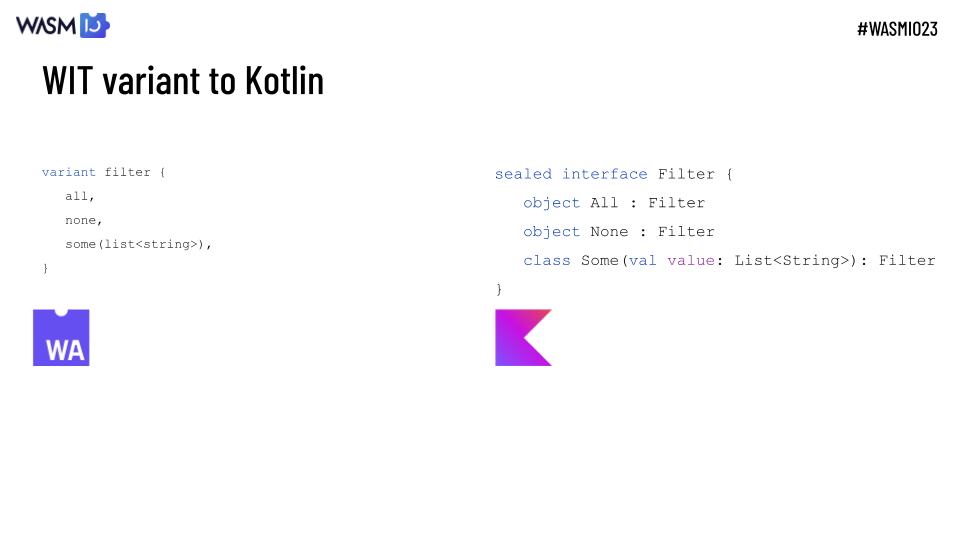

WIT variants can translate to Kotlin sealed interfaces or classes.

WIT variants can translate to Kotlin sealed interfaces or classes.

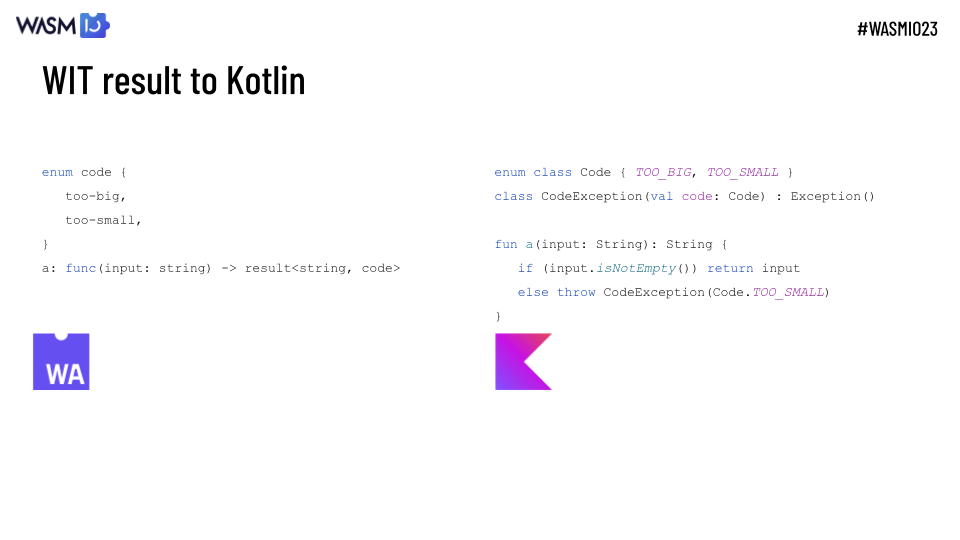

Sometimes, the matching between WIT and Kotlin could be more involved. For example, we are thinking about translating WIT results to Kotlin exceptions as shown in this code sample.

Sometimes, the matching between WIT and Kotlin could be more involved. For example, we are thinking about translating WIT results to Kotlin exceptions as shown in this code sample.

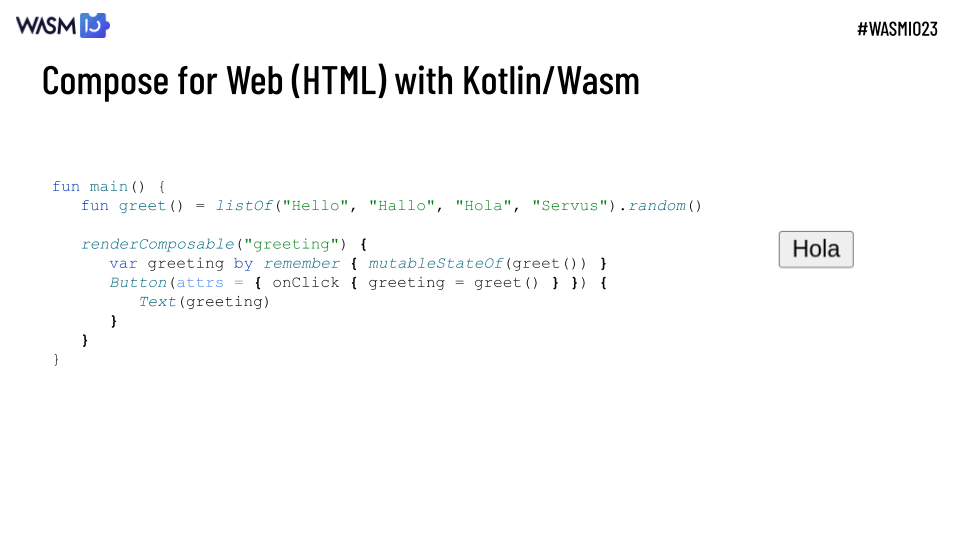

Let’s now talk about the frontend. Compose for Web provides in a nutshell 2 ways of drawing the GUI:

Let’s now talk about the frontend. Compose for Web provides in a nutshell 2 ways of drawing the GUI:

- Canvas-based pixel-perfect rendering

- HTML with DOM based rendering

While the first one is ok for let’s say build backoffices, for public websites, I tend to think we should keep using HTML lightweight rendering. Compose for Web allows targeting the DOM to build reactive interfaces as shown in the code sample above.

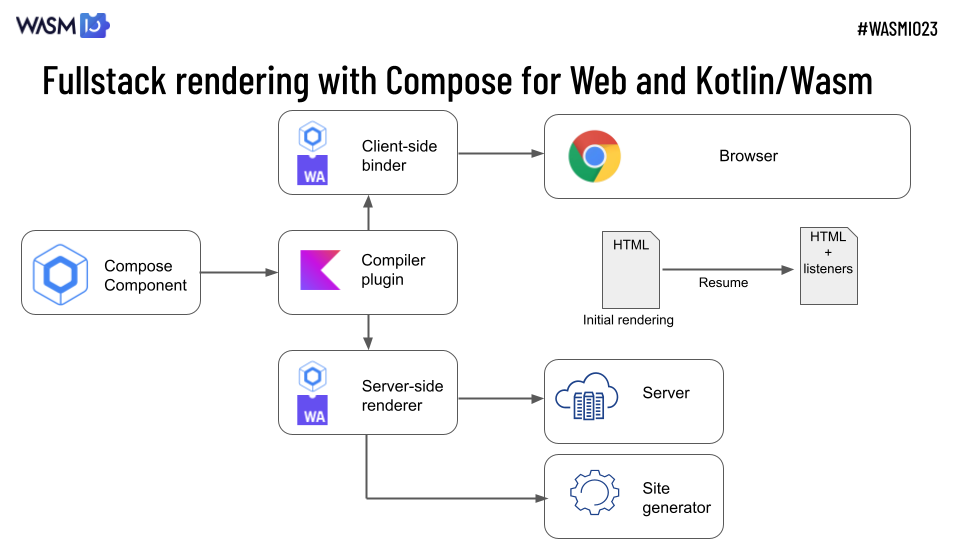

This is, for now, just an idea, but my bet is that it could be possible to evolve Compose for Web, which is currently designed as a frontend framework, to a full-stack one. I would even say to a server-side first one.

In a sense, it would be a Kotlin/Wasm reinterpretation of modern Jamstack solutions we see in the JavaScript world, providing a unified backend + frontend web framework.

The principle would be to use Compose for Web API as a server-side templating system, and to extract via a Kotlin Compiler plugin the listeners and related reactive state management code

to send to the frontend only this limited subset of the infrastructure to resume the HTML rendering done initially on server-side to add the required listeners.

What’s next? Link to heading

Let’s finish by talking about what’s next.

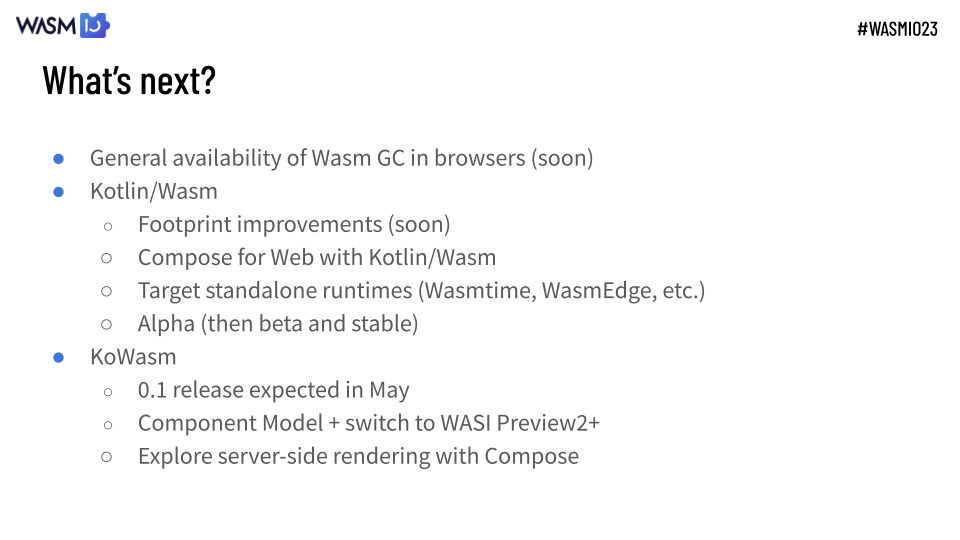

The general availability of WasmGC in browsers should happen soon and is going to be the next big step driving Kotlin/Wasm adoption.

Kotlin/Wasm is going to reduce its footprint via various optimizations. Compose is probably going to be one of the first major libraries taking advantage of Kotlin/Wasm. Kotlin/Wasm is likely going to target standalone runtimes like Wasmtime and WasmEdge, and is going to mature from experimental to alpha status.

On the KoWasm side, 0.1 release is expected around May. More work will happen on the component model and leveraging WASI Preview2+. And I would explore server-side rendering with Compose in collaboration with the JetBrains team and KobWeb project lead David Herman.

You can learn more about Kotlin/Wasm here and follow Zalim and me for fresh news about upcoming progress. Thanks!